Overview

Parables

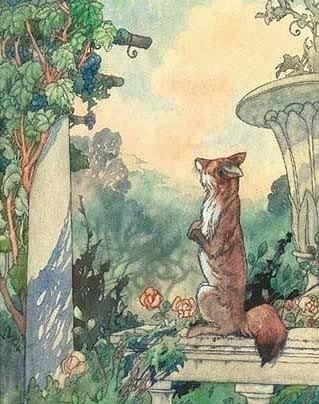

Whether the Fox got the Grapes, who now cares? Here instead are some bits of more modern wisdom.

The Phlogiston Parable

Why do things burn? Of course, because they are burnable. What could be more obvious? But that idea can be given more precise form. Some thought, There must be not only the common quality of being "burnable," but a common element that produces that quality. Many observations of burnable things confirmed the idea of a substance which was lost when something burned. The ashes of a burned piece of wood weighed less than the original piece of wood. Experiments were carried out by burning things in closed containers, and observing the results. The phlogiston theory grew to incorporate these many findings. Now, there were also substances that gained weight when being burned, but these were not thought to invalidate the phlogiston theory, a theory which explained so much! The two sets of observations simply continued side by side. Until Lavoisier in 1778 proposed the theory that something was instead added upon burning; he gave this substance the Greek name "oxygen" 1778), From this new standpoint, there were no longer two classes of things, one that lost weight when burned, and one which gained. All things, when burned, combined with oxygen. The new view explained both. It was the birth of modern chemistry.

In the 19th century, a new theory explained the formation of the most important Bible texts by a process of combination of four (or so) previously existing texts. This idea explained many observable facts about those texts. But by 1950, scholars were objecting that there were many facts which the theory did not explain. It was noticed that some situations are better explained by text growth (often called "supplementation") than by text combination. The combination theory has continued to persist, alongside those new observations. This is not desirable, but it is also not exactly anomalous. It is an old story. The Phlogiston Parable was told in detail by James Conant, in his book On Understanding Science. Let Conant draw the moral:

A concept is either modified or replaced by a better concept, never abandoned with nothing left to take its place. (p84)

It is our position that the concept of text growth (the Growth Hypothesis, GH) will explain not only the cases which the combination hypothesis explains, but other cases as well, cases for which it has proved unsatisfactory, and others in texts such as the Prophets, with which, in any case, the combination theory does not deal at all.

So far our starting point, and now, how shall we proceed? What shall we take up first? In answer to that, here is a second parable.

The Clemenceau Parable

The First World War is on. France is hard pressed. Every morning, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau convenes a staff meeting. Much requires attention - supply, injustice in military trials, troop morale - any of which could easily take up all the available time. Clemenceau had a way of clearing the air. He would open each meeting with this question

De quoi s'agit-il?

Or, what's the point here? First things must be addressed first, and the rest may be left to whoever is in charge of them. Here is a symptom of what is wrong these days: nobody, but nobody, understands the concept of Hauptprobleme. They will waste their time gladly on some trifle, while the serious unsolved loom, forever unsolved, all around them. This is a massive failure. For those paid to do it, it is a massive fraud.

In undertaking the complicated problems of the Biblical texts, we are pressed for time. We need to put our effort in places where it will do the most good, and let the rest work itself out. Above all, it is important not to rehash old findings with which we agree. Let them stand, and build on them. Do what will best advance our own inquiry.

Exactly what might advance our inquiry? First, there are some famously controversial points, such as the originality of Leviticus 2, with experts lined up on both sides, where a fresh look might produce a decision, and so add to the body of accepted results. Second, literary form. How do texts end? Some just trail off, others make a final gesture. Psalms 72 has a note at the end, "The Prayers of David, the son of Jesse, are ended." This surely marks an end, even though the text subsequently grew beyond that point. Is there a core? Judges 17-21 have been recognized as supplementary (not by that term; Soggin called them an "Appendix"). If so, what precedes? Clearly, the Twelve "Judges" (better, "Leaders") who repeatedly brought Israel back to orthodox worship. That number is surely intentional. Chapters 3-16 are then the core, indeed the groundplan, of the work. So too the Laws of Deuteronomy, as expanded from the thematic Decalogue statement in Deuteronomy 5, but that groundplan carries us only so far. What about the stuff that now follows? Third, opposition. Traditions tend to see their texts as all having a consistent message. But Samuel is notably both pro-and anti-monarchic, Ruth challenges the rejection of foreign wives in Ezra-Nehemiah, Jonah ridicules the unforgiving prophet of doom Nahum, Job doubts the whole scheme of divine justice, Micah 6:6-8 questions the validity of sacrifice, and redefines religion in ethical terms. Fourth, performance. Everyone of note in those days was literate, but most of the texts were meant to be read to others. Chapters in the major texts tend to cluster around a standard length. What conditions of performance might this imply? The Temple plaza? Someone's weekly front parlor? What is this particular text, anyway, a tract or a libretto? What does it attack; whom does it reassure?

Fifth? Well, suppose you folks out there make a suggestion. Nobody can do it all, not even us, and we would be glad to hear from the rest of you. See below.

Contact the Project