Homer

Festival CalendarThe Homeric poems are a sort of secular parallel to the Hebrew and Christian texts: a focus of devotion, and even of identity. In Classical as well as Biblical studies, this presents a problem for the Homeric investigator. The core proposition of the orthodox view is that one person, named Homer, wrote both the Iliad and the Odyssey. There are, not so much labels as swear words, for those who think otherwise. Already in antiquity, those who thought the Odyssey had a different author were called Chorizontes, or "Separatists." This treatment continues at the present time. The chief development is that the tempest now rages in a smaller teacup: the cultural prestige, not only of Homer, but of Greek and Roman antiquity in general, is no longer what it was in Gladstone's time, when Prime Ministers published volumes on the subject. The Greek language is no longer beaten bottom-first into every ministerially aspiring British schoolboy. Departments of Classics are vanishing like so many mayflies, and those that remain are increasingly used to harbor other specialties; many lack anything resembling a Homer specialist. We go with what there still is.

What may that be? One thing to be hoped for is that Homer will become open to serious inquiry. The Iliad in particular is obviously the result of an extended formation process, and tempts any historically-minded or philologically-inclined person. The Odyssey has its different charms, and it might well he appreciated for what it is, not for its failing to be a second Iliad. As we proceed, or as we look back in remembrance, here are some names to be aware of, in the long history of Homer and Homeric scholarship. The list is arranged in the form of a Festival Calendar, for those who may have room for an occasional celebratory break.

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec

Homer has been identified since antiquity as the author of the Iliad, and less certainly, of the quite different Odyssey. His birthplace is assigned to several of the Ionian islands, perhaps most commonly to Chios, just off the coast of Asia Minor (now Turkey). If we credit him with Iliad 1, we then have, not an Iliad or epic of Troy (the fall of Troy is not even mentioned in the Iliad, thought that tale was known to the author of the Odyssey), but an account of one incident in that story, the Rage (Menis) of Achilles, who being insulted by Agamemnon, refuses to join in the fighting until his sense of honor is satisfied. Much of the material in our Iliad has nothing obvious to do with the working out of that Rage, and some have sought to separate the Menis from these extraneous Books. For present purposes, we will give the name Homer to whoever was responsible for the Menis. As for the date of "Homer," one cluster of modern scholarly opinions puts him at somewhere around 0750.

Nausicaa. Samuel Butler (4 December 1835 - 18 January 1902) long ago noted the pervasive tone of feminine sensibility in the Odyssey. "As regards the mind of the writer of the Odyssey, there is nothing that impresses me more profoundly than the undercurrent of melancholy which I feel throughout it. I do not mean that the writer was always, or indeed generally, unhappy; she was often, at any rate,let us hope so, supremely happy; nevertheless there is throughout her work a sense as though the world for all its joyousness was nevertheless out of joint - an inarticulate indefinable half pathos, half baffled fury which even when lost sight of for a time soon re-asserts itself. If the Odyssey was not written without laughter, neither was it written without tears. Now that I know the writer to have been a woman, I am ashamed of myself for not having been guided by the exquisitely subtle sense of weakness as well as of strength that pervades the poem, rather than by the considerations that actually guided me." The Authoress of the Odyssey (to borrow the title of Butler's 1897 book) lived in Trapani, where tourists are still shown the sites of various Odyssean adventures, and where the ship that carried Odysseus home may still be seen in the harbor, frozen into stone by vengeful Poseidon. The Odyssey is manifestly a simpler poem than the Iliad, and whoever wrote it, it makes a good point of entry into the tangled Homeric Problem. The chief Odyssey question is whether this paean to faithful Penelope was not later given a more masculine character by adding the Telemachia (Odyssey 1-4) at the beginning of the poem, and by strengthening Telemachus' role in the slaying of the suitors at its end.

Hipparchus, the older son of the Athenian ruler Pisistratus, did not institute the Panathenaea festival, but he does seem to have been the person who arranged to have the Homeric texts, or at least the Iliad, performed in toto as part of the proceedings. That performance made the Iliad an emblem of Athenian, and soon of Greek, unity. Whatever had been its previous condition, the Iliad of the Panathenaea was undoubtedly a fixed and agreed text. That text was microscopically altered at a few points to increase the prominence of Athens in the story. The story itself was already known, but now acquired a sort of Athenian identification. As for Hipparchus, his own tale is not a peaceful one. He succeeded to the leadership of Athens on the death of his father in 0527, but was assassinated by an enemy in 0514. His legacy was enduring. The Panathenaea made Homer to the teacher of all Greece, and Athenian schoolmasters made the Iliad their textbook. "My father was anxious to see me develop into a good man,” said Niceratus (according to Xenophon, Symposium 3:5), and as means to that end, he compelled me to memorize all of Homer; and so even now I can repeat the whole Iliad and Odyssey by heart”

Euripides (05c) wrote the play Rhesus, probably his earliest work, somewhere around the year 0440). All the early dramatists, from Aeschylus on down, drew heavily on the Homeric texts for their material; the epic, here as universally, was the nurse of the drama. The Rhesus is a rewrite of Book 10 of the Iliad, a late intrusion into that text, and the later, the more likely to be popular with late audiences. Iliad 10 (the Doloneia) tells of an exploit of Diomedes and Odysseus, who killed the Trojan spy Dolon, secretly entered the Trojan camp by night, killed a newly arrived leader, King Rhesus of Thrace, and stole his wonderful horses. Euripides changed the focus, from the Greek adventurers to the slain king, and it is technically interesting to see how he adjusted the story for his drastically different performance conventions.

That the Doloneia episode was not originally part of the Iliad was seen already by the ancient critics. Which has not prevented volumes being written in its defense. One characteristic of the Dioloneia is that it gives us an Exploit (Aristeia) of Odysseus, who elsewhere in the Iliad is distinguished for other qualities (persuasiveness, ingenuity, practicality). It has been thought that this daring Odysseus represents a wish, within late Homeric circles, to bring the Iliadic Odysseus closer to the mighty figure which he cuts at the conclusion of the Odyssey, slaying many armed men who have invaded his household, and sought his wife and his position of rulership. That is, to bring the Iliad and the Odyssey closer together in he repertoire of the Homeridae, the guild of reciters who had kept both poems alive in earlier times.

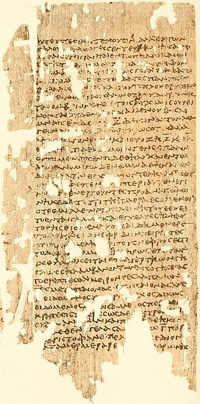

Zenodotus and the other Alexandrian critics sought to stabilize the text of the Iliad, identifying later additions by comparing the manuscripts available to them (such as Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 221, shown here). Some of their excisions seem to have been matters of taste rather than text criticism (like many modern readers, they were offended by the identically repeated lines and tended to remove one member of such pairs), but their taste, where it spotted inessential material, seems to have been pretty sound. Not a few of the lines they marked as doubtful are plausible as the additions of Athenian schoolmasters, trying to make the connections a little clearer, or expand a bit on some emotion-charged moment. Such material, as Leaf said of one passage, "explains what was already perfectly clear." However it was arrived at, the text of the Iliad established by Aristarchus, the third of the Alexandrians, became standard for centuries thereafter, and there is relatively little fluctuation from then on. The point for methodology is that Zenodotus and his successors were aware of the possibility of interpolation in these culturally central texts, sometimes on the largest scale (the Doloneia, with its different Odysseus; the Shield of Achilles, a hymn to peace rather than to war), and were sensitive to internal incongruities in the text. That awareness may be said to be the beginning of philological wisdom.

Richard Bentley (27 Jan 1662 - 14 July 1742) had an almost preternatural sense of textual incongruities. He was a contemporary of Newton (they corresponded, and Bentley wrote a popular introduction to Newton's discoveries), and a worthy parallel to Newton: it is with Bentley that the art of philology can be said to have emerged in England. Greatly esteemed in his time were the supposed Epistles of Phalarus, an ancient monarch. Bentley showed that they were full of impossibilities (such as quotes from poets who lived after Phalarus), and that the liberal tone of the Epistles contradicted the evil reputation of Phalarus in classical times. His exposure of the Epistles doomed them within the circle of the learned, though it also earned him the scorn of such as Pope. (Said Bentley of Pope's translation of the Iliad, "It is very pretty poetry, Mr Pope, but you must not call it Homer." Pope retaliated by including Bentley in his Dunciad. Bentley's skill at conjectural emendation (suggesting an alternate reading without support from a variant manuscript) was legendary, and in one instance was confirmed when a manuscript agreeing with his earlier conjecture was discovered. He planned for (and raised a certain amount of money for) a new edition of the New Testament, which would dispense with the Received Text, and be derived anew from the best manuscripts then available. This project did not see fruition, and was realized only later, under Lachmann. As might be expected of a pioneer, Bentley's reach was often further than his grasp, and many of his projects were completed only by others, sometimes with the aid of Bentley's unpublished notes. On the Homeric side, he is credited for detecting the presence of the Digamma, a sound (and letter) present in earlier Greek, and required to make the scansion work, but not represented in our written text of the Iliad. He also saw the primitiveness of the Iliad itself. He wrote in a public letter of 1743, "Take my word for it, poor Homer in those circumstances and early times had never such aspiring thoughts. He wrote a sequel of Songs and Rhapsodies, to be sung by himself for small earnings and good cheer, at Festivals and other days of Merriment; the Ilias he made for the Men, and the Odysseis for the other Sex. These loose Songs were not collected together in the form of an Epic Poem till Pisistratus's time."

Of Bentley's long tenure as Master of Trinity College, Oxford, the less said the better. Suffice it to remark that literary acumen does not always translate into administrative tact, and that administrative duty may not be the best setting for literary discovery.

Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (16 October 1752 - 27 June 1827), a historian who worked in Oriental languages as well as the Old and New Testaments, was a student of Michaelis at Göttingen (1770-1774). In addition to texts, he was also interested in the economic and social situation behind the texts. While teaching at Jena from 1775, he published on East Indian trade before Mohammed (1775) and on Arabic numismatics (1776). Over the period 1787 to 1801, he published the five volumes of his Einleutung in das Alte Testament. This revolutionized the understanding of Biblical texts by introducing the method which he called the "higher criticism;" that is, detecting the formation history of a text not from manuscript variants (the "lower criticism"), but from indications in the texts themselves, such as permit the detection of interpolations. He notes, in the preface to his second volume, that he had finally come to see that the Biblical texts were themselves the result of a complex process, in which they "passed through several hands." So have texts in every other language; this growth process is something like a universal in every corner of antiquity. The importance of the work was immediately recognized, not only in Germany but elsewhere; Eichhorn was elected an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1825. Directly following the publication of the first volume of the Einleitung, in 1788, he received a regular professorship at Göttingen. The stage was then set for something no less remarkable in the history of Homeric study.

Friedrich August Wolf (15 February 1759 - 8 August 1824), at the age of eighteen (1777), following years of private study, entered the Department of Philology at the University of Göttingen, the catch being that there was no such department (this was a year before Eichhorn arrived there). After graduation, during his first teaching years at Halle (1783-1807) he defined what he meant by philology - "the study of human nature as exhibited in antiquity." This was revolutionary. It brought together all study of antiquity, regardless of the languages in which various ancient texts might have been written. With others, Wolf was excited by the publication of the Venetian Scholia by VIlloison in 1788; this made available the early Alexandrian scholarship on the Homeric texts, and was quick to draw conclusions. Wolf's Prolegomena to Homer (1795) created a sensation. Contemporaries like Heyne had seen the Alexandrians merely as one more stage in the corruption of the Homeric text. But as Grafton and others noted in the Introduction to their translation of the Prolegomena, "Wolf by contrast wrote the first 'history of a text in antiquity.' He tried to show what the rhapsodes, the diaskeuastai [revisers], and the Alexandrians in turn thought they were doing with the original poems. He imagined with as much vividness as his sources permitted what it was like to be a professional reciter in a society passing from orality to literacy; what it was like to be a textual critic in a world without manuals of the ars critica, criteria for assessing the age and independence of manuscripts, and printing presses. Far more than Heyne's lectures - or than any of the other responses to Villoison's edition - the Prolegomena was the history of the Homeric text, at once philological and literary in inspiration, that Villoison had dreamed of helping to create." Wolf's Prolegomena appeared in 1795; In it, he several times refers to the parallels in Eichhorn's Einleitung. The Prolegomena, in turn, largely defined the path that Homeric scholarship would take from then on.

Karl Lachmann (4 March 1793 - 13 March 1851) brought further scientific rigor to textual criticism, the reconstitution of a text from variant manuscripts. He made a mark in three fields: mediaeval German poetry, including such figures as Walter von der Vogelweide (1827); New Testament (his edition of 1831, revised in 1842 and 1850, carried out Bentley's unfulfilled plan of editing the text anew from the best available manuscripts), and Classics (his 1850 edition of Lucretius was a widely admired masterpiece). He has been much criticized by a perhaps envious posterity, but as Wilamowitz said, at the end of a rather caustic account, in his history of philology, "Where would we be without Lachmann?" Lachmann's notes on Homer's Iliad appeared in 1837 and 1841, and with support from his work on the Nibelungenlied and other sagas, posited that the poem originally had the form of eighteen separate lays. Neither his eighteen, nor the sixteen of Koechly (1861), nor any of several other attempts along this line has proved convincing. But the basic idea, that the gigantic final Iliad was not improvised in a day, but rested on a tradition of more modest performance pieces, was sound. It was one more step in the direction already foreseen by Bentley.

Adolf Kirchhoff (6 January 1826 - 20 February 1908), a Berliner whose professional life was spent as Professor of Classical Philology at the University of Berlin, was a student of inscriptions (he edited one section of the Corpus Inscriptionum Atticarum), and of Greek tragedy (he produced the first critical edition of Euripides in 1855, and later edited Aeschylus (1880), as well as Hesiod's Works and Days (1881). He was a statesman of the field, and edited the journal Hermes from 1866 to 1881. For his notable services, he was elected an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1888. Still later came his study of the sources of Thucydides (1895). But his major monument is Die Homerische Odyssee (1859), in which for the first time the unitary view of that text was challenged in detail. His work, like that of his older contemporary Lachmann, marks a major advance: it sees the Odyssey not as a poem, but as the end product of a formation process. The core of Kirchhoff's analysis was to doubt the originality of the Telemachia (Books 1-4), and of other features of the text that tended to emphasize the importance of Telemachy This was not quite right: the Telemachia was original, but that and other Telemachus passages were later expanded, But, hey, one step at a time. First you turn on the light, and then you and others can see what it may reveal.

Heinrich Schliemann (6 Jan 1822 - 26 December 1890) turned the light on Troy itself. He had been fascinated by the Iliad since his youth. He became a businessman in order to amass enough of a fortune to pursue that fascination; he also traveled extensively. Then those funds, and that experience, in hand, and following up on earlier work, he began in 1872, with an army of 300 engineers and workers, to dig for Troy at modern Hissarlik. Troy he did indeed find. He did further excavations at Mycenae (uncovering the palace of Agamemnon), and at Tiryns. Not everything he found was genuine, and not all his claims of unaided discovery were true. Schliemann had the headline instinct. But, instinct and all, be brought archaeology unavoidably to the attention of the Homerists. More precisely, he introduced scientific method into the study of the Homeric textual tradition. To this day, it is easier to find rationality among the archaeologists than among those who call themselves Homerists.

Walter Leaf (26 November 1852 - 8 March 1927), in addition to his work on the Iliad, had a distinguished career as a banker; he served as president of both the International Chamber of Commerce and the Classical Association. He was regarded as the leading Homerist of his day. His edition of the Iliad (1886-1888) was long considered standard, as was his translation, done with Andrew Lang and Ernest Myers (1892, 1911). His theories of the formation of the Iliad are conveniently set forth in his Companion to the Iliad for English Readers (1892). He considered that the Menis (the Rage of Achilleus) was the oldest part of the poem, and the only part due to Homer; everything else being later additions. Leaf went very far in stripping the Iliad of anything not directly relevant to the Menis, the rage of Achilles. He considered that the Greek Wall was a later addition, that Patroclus' body was not recovered, nor had Patroclus been wearing Achilleus' armor, hence there was no need for the Shield of Achilles passage. Nor was there, originally, an Embassy to Achilles (Iliad 9). For Leaf, the Menis comprised Books 1, part of 2, 11, part of 15, 16, and 22.

William D Geddes (21 November 1828 - 9 February 1900) was born in Aberdeen, and from 1860 was a Professor (from 1885, Principal) at the University of Aberdeen. He did much to raise the standard of the teaching of Greek in Scotland, both at schools and at the early Scottish universities. His 1855 Greek Grammar was in its 17th edition by 1883 (revised edition 1893). On the textual level, his edition of Plato's Phaedo (1885) was highly esteemed. He also published much on Celtic lore and tradition, and was knighted in 1892. In 1878 appeared the closely argued Problem of the Homeric Poems, in which he largely followed the view of George Grote (17 November 1794 - 18 June 1871), whose History of Greece began to appear in 1846, that the Iliad consisted of an original core (which Geddes called the Achlleid), plus later additions. Geddes introduced the idea that the additions represented influence from the Odyssey; he called these the "Ulyssean" portions of the Iliad. For Geddes, the original Iliad comprised Books 1, 8, and 11-22.

Many observations in both these books retain their usefulness, and are recommended for current study. Leaf's caution (Companion 28f) remains not only valid, but urgently so:

"It must not be supposed then that because we say that a certain passage is "late," or is "an addition," or even an "interpolation," it is therefore inferior . . . . In fact, among the parts of the Iliad which are always recognised as the latest, we find as a rule most of the passages of noble pathos which sink deepest into our hearts."

What is fatal to both these models is the conviction that its earliest stratum is by "Homer." Internal evidence and economic considerations alike suggest that "Homer" is the author of the Menis (the Rage of Achilles), the "monumental composer" of recent theory; but that his work rests on, and in its way focuses, a long previous bardic tradition of shorter performance modules.

Florence Melian Stawell (2 May 1869 - 9 June 1936), of a distinguished Australian family, studied in England, and won honors in classics in 1898 (she is pictured above on that occasion), but being frail and of indifferent health, worked mostly in private. Her philosophical convictions are revealed by the fact that from 1896 through 1931, she published regularly, up to five times a year, in the International Journal of Ethics. In Homer, she was a follower of Walter Leaf, but her 1909 book Homer and the Iliad (almost half of which is devoted to the Odyssey), restored some of the early books which Leaf had excised as late. She did not hesitate over the Doloneia, nor was she, in re-including Iliad 2, fooled by the long interpolation at lines 93-454. She would have nothing to do with Separate Authorship; for her it was all Homer, and this led her to a defense of the ethically positive Iliad 23-24 (rightly rejected by Leaf), to provide an ethically positive conclusion for the otherwise violent Iliad. Elsewhere, her sensibility served her well. Though rejecting Butler's 1896 "Authoress" proposal, she twice quotes him favorably on certain passages, and herself gives an exquisitely insightful account of the tense relationship between Telemachus and his mother. Her 1909 book was virtually ignored by the academic establishment; the only English-language response was a mildly dismissive note in the Burlington Magazine. The one academic review was in Czech (Hoffmeistr, 1911), and did not even spell her name right. In 1928, following suggestions by Arthur Evans, she published in The American Journal of Archaeology an argument that all three Minoan scripts were in Greek. This was followed by a 1931 book, which did get academic attention: it was ridiculed in the Classical Review by none other than Michael Ventris. Her literary translations in this period gained more respect; a 1928 translation of Iphigenia in Aulis (with music from Gluck), was praised by E M Forster, and her joint book (with G Lowes Dickinson) on Goethe and Faust was lauded by Morgan (in Modern Language Review) as getting at the heart not only of the play, but of the German character. Her sensibility was not confined to Greek alone, nor only to antiquity. When comes such another?

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (22 December 1848 - 25 September 1931), an indefatigable reader, once greeted a young student who had come to visit him by bounding down the stairs, early in the morning, and asking, "What are you reading?" His own reading was tremendous; and he not only read but remembered: his 1921 History of Classical Philology (translated in 1982 as History of Classical Scholarship) was apparently written from memory. His first publications were on Euripides and the other dramatists, but the center of his work was Homer, from the Homerische Untersuchungen of 1884 (a preparatory work on the Odyssey), to the concluding Die Ilias und Homer of 1916. Wilamowitz, like Stawell, saw the Homeric texts as the end result of a formation process - he so hated the Unitarians that he never refers to them. He offers us a complex picture of that formation process; so complex as to be self-defeating for many readers. Which is not to say that is too complex; unwary would be the later researcher who publishes on a line of Homer without checking to see what Wilamowitz thought of it. In addition to his philological acumen, Wilamowitz was not immune to the attractions of mere literary beauty. So far, so forgivable, but like so many, not taking Leaf's warning seriously, be tended to believe that what is beautiful must also be true - or in this case, authentic. Applied to the Shield of Achilles in Iliad 18, this produces philologically questionable results. Wilamowitz first taught at Greifswald (1876), and later at Göttingen (1883). He assisted his Greifswald colleague and friend Julius Wellhausen (the Untersuchungen of 1884 are dedicated to him), who was theologically uncomfortable at Greifswald, to move to Göttingen as well. His final appointment was at Berlin (1897), from which he retired in 1921, the year in which he wrote the History. His concluding characterization of the ideal scholar in the History - vir bonus discendi peritus (itself a take on Cato's description of the ideal orator - vir bonus, dicendi peritus), may or may not be an echo of Housman's 1911 Cambridge inaugural address, where the same phrase had appeared. (Either way, be it noted that Wilmowotz' correspondence with Housman, as with many others, has been preserved and published).

Tempo. Not all advances in scholarship come from scholars. The Homeric poems are not poems, they are performance pieces, and we also need to hear from musicians. In December 1905, a live presentation of part of Iliad 17 was given at the Berlin Opera House "Unter den Linden." It turned out that the rate of delivery on that occasion was about 6 seconds per hexameter line; that is, one syllable per standard heartbeat. Subsequent testing by the present writer (with the cooperation of several living Homerists) has confirmed that, though singers can go faster, this heartbeat tempo is near to the rate of maximum audience intelligibility. The Homeric poems were for long the property of a guild of reciters (the "Homeridae" of legend), and it may be assumed that, as with the centuries-long performance tradition of the Biblical Psalms, not only diction, but tempo, remained more or less constant over time. Then to get the approximate performance time for any part of the Iliad or the Odyssey, however far back that part may be thought to go, we simply divide the line count by 10 to get the time in minutes. Iliad Book 1, which with small exceptions seems to be more or less intact as first composed, and which in our text consists of 611 lines, would then represent a performance session of 61 minutes: about an hour. A majority of our present Iliad Books will fit something like that time slot. The ten Books which time out at much over an hour (2, 5, 9, 11, 13, 15-17, and 23-24), require special attention.

Denys Page (11 May 1908 - 6 July 1978), a student of Gilbert Murray at Christ Church, Oxford, where he had a distinguished undergraduate career, winning every prize in sight in 1928, and a First in Literae Humaniores in 1930. He studied in Vienna under Ludwig Rademacher, then returned to Oxford, where was appointed a Junior Censor in 1937. Tense times ensued. He married Katharine Dohan in Rome in 1939, but that same year was assigned to the Bletchley Park codebreaking operation, becoming head of section ISOS and a member of the XX Committee in 1942, and Assistant Director in 1944. Returning to academic life, he reached the distinguished position of Regius Professor of Greek at Cambridge in 1950, and was Master of Jesus College from 1959 to 1973. He was knighted in 1971, become that year President of the British Academy until 1974 (he had been a Fellow since 1952).

To the Odyssey, Page brought not only a codebreaker's sense, but a devastating wit. In his Sather lectures at the University of California (published as The Homeric Odyssey, 1955), he made fun of the absurdities in the present text, but also showed how they might have arisen. He realized that the Odyssey, though not as long as the Iliad, was equally unperformable as a whole, and was instead a repertoire of possible performances, and that in extracting one module for separate performance, a reciter might add explanatory material - either totally irrelevant or borrowed from the wrong place in the rest of the poem - to explain things to the audience. He is under no illusion that Book 1 is an afterthought, but sees that it most effectively introduces what follows.

Geoffrey Kirk (3 December 1921 - 10 March 2003). Ulysses S Grant wrote his memoirs, entirely omitting his two terms as President of his country (during which time, among other things, he established the system for international arbitration of maritime disputes), and mentioned only his service in the earlier Civil war. Noted Homerist Geoffrey Kirk also wrote a memoir, Towards the Aegean Sea, which dealt solely with his service during World War 2, where he and others in disguised and heavily armed local schooners sailed up and down the Cyclades Islands, off the east coast of Greece, and as far as the coast of Turkey (ancient Ionia), landing assault parties, attacking Germans, and rescuing partisans. His service in the ranks of Homerists nevertheless deserves a word. In that second service, like Grant, he reached the top. He took his degree after returning from the war, in 1946, was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1959 (Vice President, 1972-1973), and reached the pinnacle, the Regius Professorship of Greek at Cambridge, in 1974, retiring in 1982. His first work was on the Greek philosophers, Heraclitus (1954) and the Presocratics (1957). He then turned to Homer, with The Songs of Homer (1962, revised as Homer and the Epic, 1965); an edited collection, Language and Background of Homer (1964); several studies on myth (1970, 1974); and Homer and the Oral Tradition (1976). His 1962 view of the Iliad was complicated by the need to address recent "oralist" approaches (A B Lord was one of the readers of his manuscript), and the Mycenaean world recently revealed by the Linear B decipherment (John Chadwick was another reader). He wound up, in 1962, with a vision of a gradually accumulating Iliad.

Whatever may be the truth about the Iliad and its formation process, students want a simple view, and scholars want a commentary in which every line of the text is addressed, never mind whether it is early or late in the text's history. Hence the rather rueful note prefacing the first volume (1986) of the six-volume Iliad commentary which Kirk oversaw as the first fruits of his retirement, and to which he contributed the part on Iliad 1-8. It reads, "the author may be thought to be adopting in this volume a somewhat more "unitarian" approach to the Iliad than he has in earlier writing. That reflects, perhaps, a small change in his own position, but primarily it is because, other things being equal and for one who is hoping to produce helpful and objective comments, it is better to err on the side of conservatism, of treating the text as a reasonable reflection of Homer's own poem."

Martin West (23 September 1937 - 13 July 2015) took a wide, and also a deep, view of Greek tradition. He explored its Asiatic components in Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient (1971; translated into Italian in 1993), and again in The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth (1997), which noted parallels in Biblical and Babylonian texts. Old Testament parallels to Homer and Hesiod had been pointed out long before by Zachary Bogan (1658), but this had left no mark on Homeric scholarship. Said West, "In those days, of course, it was common enough for Latin, Greek, and Hebrew to be studied in parallel. From the late eighteenth century, Classical studies became more isolationist. Works such as Bogan's were forgotten, or at any rate left unopened; I do not know whether anyone but myself has read him in the last two hundred years." An important source of information abort epic is early lyric, and West's study of Greek Lyric Poetry appeared in 1993. Unlike many Classicists, he recognized the importance of performance in early Greek poetry, and wrote a study of Ancient Greek Music in 1994. Said he in the Introduction, "Ancient Greek culture was permeated with music. Probably no other people in history has made more frequent reference to music and musical activity in its literature and art. Yet the subject is practically ignored by nearly all who study that culture or teach about it." He returned to the subject in 2001, with Documents of Ancient Greek Music: The Extant Melodies and Fragments (with Egert Pohlmann). His edition of Homer (Homeri Ilias) was published by Teubner in 1998 and 2000, followed by Studies in the Text and Transmission of the Iliad (De Gruyter, 2001). Translations of the Homeric Hymns and Greek Epic Fragments (both Loeb) appeared in 2003. Two overviews followed, The Making of the Iliad in 2011 and The Making of the Odyssey in 2014. The latter was not altogether complimentary: "The poet of the Odyssey was a seriously flawed genius. He had a wonderfully inventive imagination, a gift for pictorial detail and for introducing naturalistic elements into epic dialogue, and a grand architectural plan for the poem. He was also a slapdash artist, often copying verses from the Iliad or from himself without close attention to their suitability . . . " The matter of common lines in the Odyssey, and between it and the Iliad, indeed, the whole subject of what are sometimes called "formulas," remains a matter for further investigation. West's edited text of the Odyssey, the capstone of his work on the basic Homeric corpus, appeared posthumously from De Gruyter in 2017.

Stephanie West met her husband Martin at a lecture by Eduard Fraenkel at Oxford in 1960. Martin's first trip to Greece was in that same year. He had memorized one of two surviving Delphic Paean melodies, and . . .

"on arriving at Delphi I sang it at the top of my voice in the ruins of the sanctuary where it had had its premiere 2,084 springs previously. My two traveling companions distanced themselves somewhat. A little later, as we examined the stone on which the text is inscribed, one of them stumbled against it, and it nearly crashed from its moorings and shattered. (I married her all the same)."

Her first publication was The Ptolemaic Papyri of Homer (1967), and Homer has remained a major emphasis, along with Herodotus (Demythologisation in Herodotus, 2002) and Lycophon. She was Classics Tutor at Hertford College (Oxford) from 1966 to 2005, and from 1981 to 2005, also a Lecturer in Greek at Keble College (Oxford). She was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1990, and made a Foreign Member of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2012.

Theirs was that rare thing in academe: a collaborative marriage. Each publicly acknowledged the assistance of the other. Said Stephanie at the end of the Prefatory Note to her commentary on Odyssey 1-4, "But my greatest debt is to my husband, Martin, whose patience, learning, and lucidity have repeatedly extricated me from difficulty." She had replaced the unexpectedly deceased Douglas Young (1913-1973) in the Odyssey commentary of Alfred Heubeck and others (6v in Italian, 1981; 3v English translation, 1988, 1989, 1992). Hers, as it happened, was the responsibility for Books 1-4, the controversial Telemachia. The group leader, Heubeck, was a firm believer in the unitary view of the Odyssey, and thus of the originality of the Telemachia, with all the questions it raises about the prominence of Telemachus in the story. Stephanie duly notes that the Telemachia is essential to the Odyssey as we have it. But on p51, she registers this dissent: "The prominent part which [Telemachus] plays in our Odyssey leaves Penelope little more than an onlooker, though vestiges remain of an earlier version in which she was Odysseus' accomplice in exacting vengeance from the suitors."

Her involvement was at least how the suitors saw it. Here is their testimony, as it stands in Odyssey 24:125-129, 167-172 (Lattimore's version):

We were courting the wife of Odysseus, who had been long gone.

She would not refuse the hateful marriage, nor would she bring it

about, but she was planning death and black destruction

with this other stratagem of her heart's devising:

She set up a great loom in her palace, and set to weaving . . .Then in the craftiness of his mind, [Odysseus] urged his lady

to set the bow and the gray iron in front of the suitors,

the contest for us ill-fated men, the start of our slaughter.

Not one of us was able to hook the string on the powerful

bow, but all of us were found far too weak for it.But when the great bow was given into the hands of Odysseus . . .

So goes the past; let these and other contributions be remembered, as others do what they can, in their turn, with these famous perplexities.